Butterfly Myths: stories about my artist mom

JOAN MARIE SCELP STARR CARTWRIGHT LAURIA (b.1929, d.2012), my mother, was a jazz singer. As you might expect though, other people knew more about that part of her life than might an adolescent boy – I wasn’t old enough to see her perform in the bars and night clubs of the small, Eastern Ohio town where we lived. But I wrote a little about what I remember here.

In the beginning, she led a romantic life, compared to others in a small town, anyhow. I remember as a child seeing her transformed, walking out the door to go sing in East Liverpool’s night clubs, my own movie Starr, dressed to the nines.

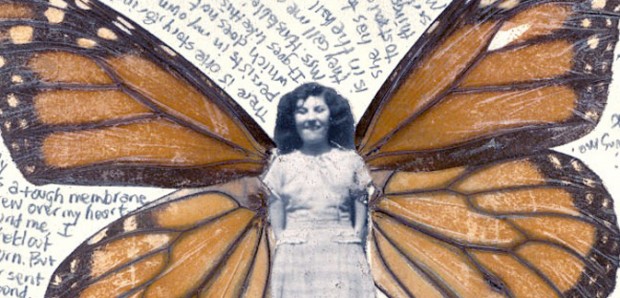

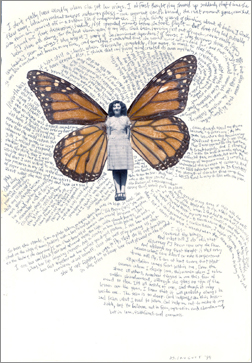

A Butterfly Mythology

My experience of her as that beautiful but elusive, ever-changing being compelled me to create a whole body of work, all under the title The Butterfly Myths: a series of collages, a screenplay, and now in progress, my first novel, a cautionary tale about trying to escape who you really are, about trading in your dreams for something safer.

My experience of her as that beautiful but elusive, ever-changing being compelled me to create a whole body of work, all under the title The Butterfly Myths: a series of collages, a screenplay, and now in progress, my first novel, a cautionary tale about trying to escape who you really are, about trading in your dreams for something safer.

For a while there, in the ’60s, my mother was married to the mob, (but it may still be too soon to name names, so I won’t). It was Mob Guy she’d left, briefly, to reconcile with my father, to flee Ohio, and come with us to Texas – only to return a few days later to avoid threats to her, my sister, and I.

Mob Guy, my step-father, could have been the model for Henry Hill, the character played by Ray Liotta in Goodfellas whose Irish blood prevented him from being a made man, but who was still allowed into the inner circle.

He must have done something to endear himself to them or in some other way make himself of value, as he certainly didn’t demonstrate much in the way of brains. My mother later told me the story of how once, for about a week or two, they had to “get outta Dodge,” in this case East Liverpool, because he’d skimmed a little of the take from one of the businesses he was watching for them. Yet the guy lived another six or seven years and died of a heart attack (not retribution – when they’d do it, they might not want you to be able to prove they did it, but they’d certainly want you to know they did it).

Either way, that was later, after she’d returned to him in Ohio. But in 1962, during that week or so that she was with us in Texas, he was apparently still “connected” enough to call in a favor, in the way you might ask your cousin, the attorney, to whip out a quick letter threatening legal action against someone with whom you had a disagreement.

In other words, it was probably a somewhat idle threat. I doubt the Pittsburgh office of the Mafia owed my step-father anything more than just the phone call to my mother. He would have probably had to follow through with the rough stuff on his own dime, and I really don’t know if he’d have bothered.

Still, my mother was a beautiful woman with dreams of a career on stage, so the promise of having acid thrown in her face did the trick: she gave in and went back to Ohio. I wonder to this day if any violence that might have been visited on my sister and I would have been considered merely collateral damage.

Fly, Butterfly, Fly Away

I didn’t know until much later that she’d been running all her life, and that the more important story wasn’t about escaping to Akron with embezzled cash, to her mother Rose in Cleveland, or even to Dallas. The more important story, to me, was the one about a gifted young woman who crushed her own soul, gave up her creative gift in order to be comfortable and secure, and in the end lost all of it. It may very well be one reason why I persist as an artist.

She knew I would eventually tell the story, some version of it at least. In fact, she helped while she still could, filling in details on everything from growing up in the depression-era steel mill town of Midland, Pennsylvania, to what it felt like having the mob track you down in Dallas just from the wedding ring you hocked. But now that she’s gone, along with most of the other people who played a role in her life, I can tell that more compelling story without fear of offending.

Doing research for my novel’s details on clothing, housing, and general living condition in so-called company houses, I came across an entire series of photos in the Library of Congress documenting day to day life in my mother’s hometown, and from right around the time that her story begins. I’m compiling those, along with other background details, on a Facebook Page dedicated to the process of writing it all out, also titled The Butterfly Myths. I invite you to visit it now.

“Children in Midland, Pennsylvania,” photographed by Jack Delano, January 1940, for the U.S. Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information