Yen-Hua Lee’s Tales of the Severed Finger

and Other Injuries Too Close To Home

Yen-Hua Lee took her position before Quin Mathews’ lens, and the filmmaker asked his ice-breaker question. About that missing tip from her right index finger. On the wall behind her were arrayed fifty-five framed drawings, the bulk of her freshly hung, works-on-paper exhibition at the Dallas Contemporary.

Without hesitating, she held the hand up to his camera and, as if reporting live for EyeWitness News, too coolly described that moment when at the age of three she’d gone to call her father for dinner; and how because he couldn’t hear her above the noise of the power saw, she placed one hand on his work and as she put it, that finger went bye-bye.

Taiwanese and constantly on the move to keep her H1-B work visa, Lee was down from New York to install her work in the Contemporary’s current Mix! exhibition, the series devoted to culturally and/or ethnically diverse artists. While everything in the show takes her signature style of fairy tales in black-and-red ink, this grouping mimics a Grimm’s more than anything she’s done before. For one thing, each narrative picture is executed on a leaf detached from a second-hand copy of the 1925 memoir, My Life and Memories. And in hanging them, she’s jammed all fifty-five frames one against the other, like she was trying to push the whole disjointed thing back together again.

In these works we see Lee turning away from her own pain to draw on the personal dramas of her friends, but with that same unemotional, unaffected voice of the collaterally damaged child. It is authentic; not the narrative style we think children use, but the one they actually do; one we’ve seen so many times on the ten o’clock news and reality TV, like A&E’s Intervention and Sundance’s Sin City Law; one that’s preternaturally detached, maybe even somewhat objective. How else could a child bear witness of such crazy things? As if willing to go on-camera but not to risk her own innocence, little Yen-Hua narrates docudramas complete with all the blood, sweat and tears, always making sure not a drop gets on (or comes from) her. It’s obvious how much it must hurt, defense mechanisms being the fairly reliable gauges they are.

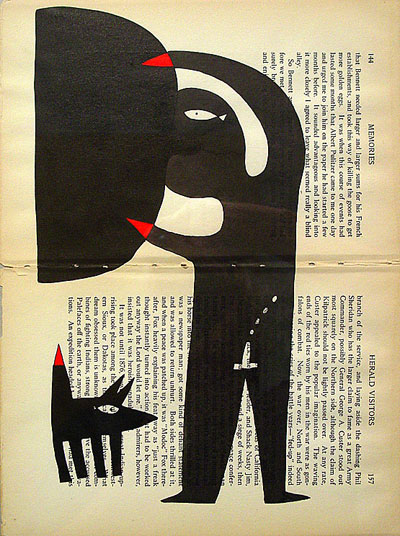

So the overflow of emotion one would normally expect to accompany such a surfeit of bodily fluids instead gets bottled up inside Lee, then once uncorked, she tamps down in the mute flat faces of her two-dimensional figures. It’s like we’ve just tuned in for the unintelligible but cathartic release of a Spanish soap, only to find all the parts played by IKEA Man. Still, we like to look, especially when all the intimate details are veiled behind thick symbology. Take for instance those red, knifelike hands her actors embed in one another. You always hurt the one you love, goes the torch song my nightclub-singing mother used to do.

But the rest is a fable to engross you for hours, with dense, iconic imagery that emanates either from the back of Lee’s occipital lobe or the front of Gabriel García Márquez’s: meddling birds & beasts, internal organs shaped like Monopoly houses, and an awful lot of nipples. People seem to be living with each other, loving each other and comforting each other but hurting each other at the same time. It’s a wonderful life and we all want to get along, but everyone’s got blood on his hands.

Even with all the mystery, though, the best of Lee’s works read as clearly as the great graphic posters of Europe, and especially those of Switzerland during the ’70s and ’80s, sans all the Helvetica. So you really can decipher the basic features of whatever’s being sold.

That’s not to say they’re all cool and humorless, though, as I might also liken them to bawdy, vaudevillian shadow-puppet acts. One of my favorites portrays a male figure grasping, and sucking on, what appears to be a very large breast, maybe it’s just me. Depending upon which is to proper scale, the male or the mammary – and upon which fluid he’s passing – he might be infant son or husband, it could be a poster for Health class or for Sex Education, and Mae West might be saying, “Is it feeding time or are you just glad to see me?”

Perhaps that’s where Lee ran into a wall. While their simplified bodies are predominantly rendered as blacked-out silhouettes, her inky figures are, at least in a Mies van der Rohe-minimalist kind of way, anatomically correct, with penises seemingly styled after t-shaped corkscrews and Featuring Vaginas by O’Keeffe. Consequently, while Lee’s clear intent is mostly to help us tell the boys from the girls, the Contemporary said they’d determined the sex to be problematic enough, in Dallas at least, for her work to be sequestered in a side hall, not shown in the main corridor where Mix! artists usually exhibit, and also partitioned with an adult content sign. Consider yourself forewarned.

My own daughter almost, just almost, lost one of her fingertips to the heavy steel door at day care when she was a toddler. I was thankful it was across the street from a hospital. Now the faint scar across her loops and whorls proves they were successful in reattaching it, and there’s little else besides her parent’s retelling to remind her that it even happened. But it didn’t work out that way for Lee. Her mother knew to put the severed tip on ice but was nonetheless unable to save it, and from her narration I deduce she remembers much of the experience.

So I wonder how much the trauma may have made her the artist she is today, compelled to describe the pain of life in a detached way and from a safe distance. I remember, in Quin’s interview, that she held up that right hand at arm’s length, blocking her face from the lens. And she continued to use it as a shield, not only while telling its story but also after, as she changed the subject to her work. He finally had to tell her she could drop it.